Brave New Worlds: The Mira Cluster

“And as the eyes of God bled with celestial ichor and the fickle flames of wandering stars broken loose from their posts charred the earth to dust, so too did the Ruin Author raze the erstwhile gardens of Paradise to dust.“

Inscription ‘Uranoscopus’, Horizon (c. 945,000 years before present)

The Splendor of Life

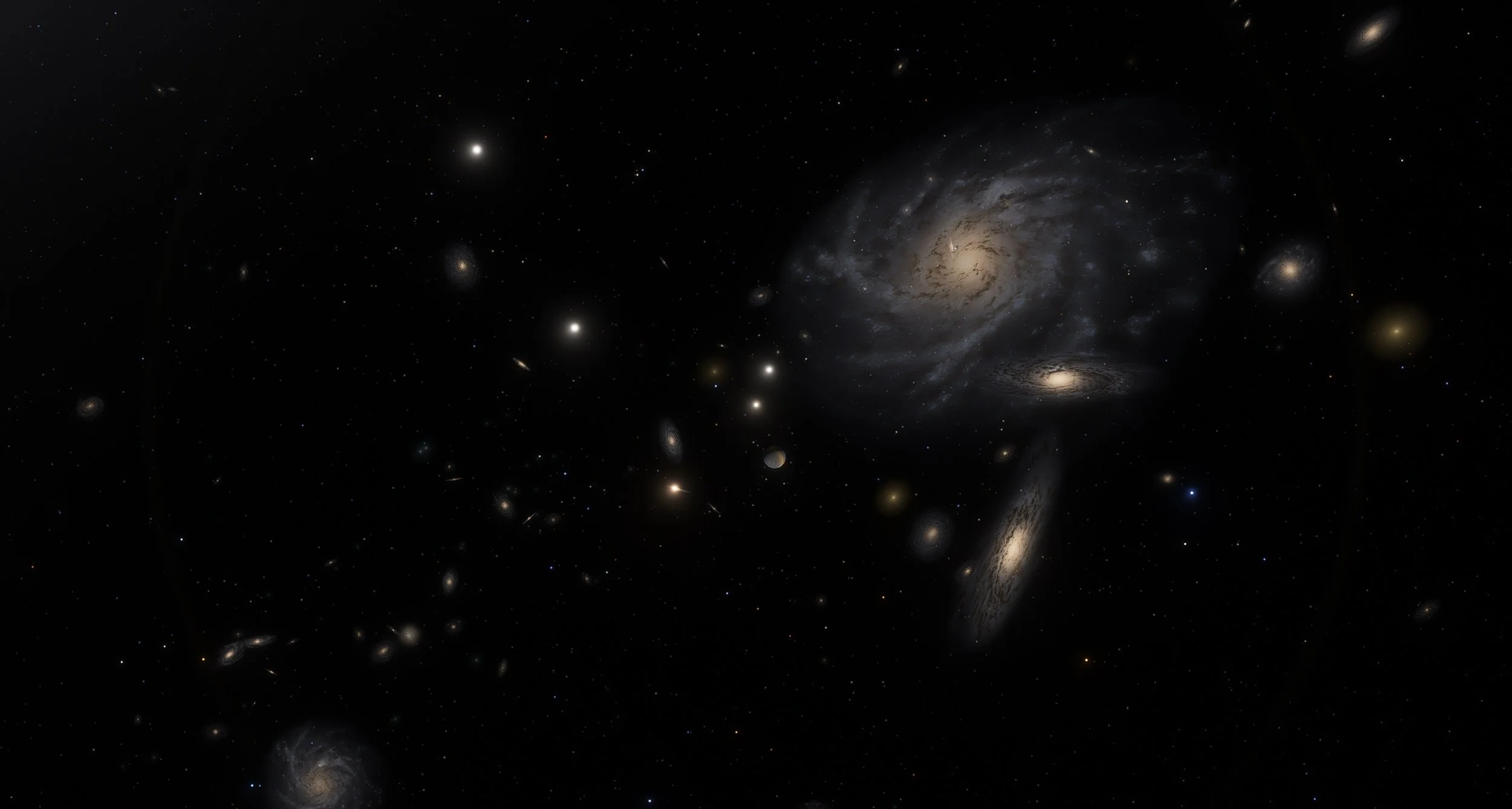

A cold Jovian world orbiting an orphan star in the depths of the Mira Cluster makes for a spectacular vantage point to observe this stellar megalopolis. Dominating the field is the great spiral Helianthus, looming large even a million light-years away.

Lying around 9 billion light-years away from Earth in the constellation of Ursa Major is a nondescript region of space that will, two billion years from now, give rise to a rare splendor known as the Mira Cluster.

In its time, Mira is one of nine great galaxy clouds of its supercluster. It is similar to our own Virgo Cluster, albeit a bit larger and more populous. A huge diversity of galaxies calls this cluster home, from tiny dwarf ellipticals untouched since the dawn of time to enormous giant spirals blazing with the light of trillions of alien suns.

There is, however, one key difference that sets the Mira Cluster apart from its familiar kin. While most galaxy clusters in our local universe are dominated by old, red elliptical and lenticular galaxies that have remained mostly unchanged for billions of years, the Mira Cluster is dominated by active, youthful spiral and irregular galaxies. Over 90% of its large members are star-forming galaxies, many of which are starbursts furiously assembling nascent solar systems at rates up to a thousand times faster than our own Milky Way. Mira’s supermassive black holes are also working overtime - . It contains seven quasars, sixty Seyfert galaxies, and twenty LINER galaxies in comparison to the 5-10 active galactic nuclei expected for a cluster of its size.

Thanks to this abundance of activity, Mira shines as bright as forty Virgo Clusters combined. Amazingly, over half of its total light output comes from one galaxy, Sarcodes, whose central black hole Astronesthes shines with the overpowering brightness of nearly three thousand Milky Ways as it devours 10 solar masses of hot gas every year.

Fanning the Flames of Eternity

A chunk of the real-world Coma Cluster (Abell 1656), 300 million light-years from Earth. This is how most galaxy clusters appear - a uniform spread of smooth, reddish galaxies devoid of dust, nebulae, or young blue stars. Mira does not look anything like this.

By all rights, a cluster such as this should be a place that galaxies go to die. Between frequent galactic collisions, ram-pressure stripping from the intracluster medium, and frequent black hole outbursts, conditions in dense clusters conspire to extinguish star formation and reduce galaxies to burnt-out cinders. Mira is in an earlier stage of evolution than, say, the Coma Cluster, but the more comparable Virgo still has an extensive array of old galaxies which Mira lacks.

As galaxies move through the hot envelope of a cluster, they experience a wind force that strips their outer regions of star-forming gases. Ram-pressure stripping is mostly responsible for extinguishing small galaxies and is hard at work within Mira - more than a third of its star-forming dwarf galaxies are moderately to severely stripped, while even larger jellyfish galaxies ravaged by ram-pressure stripping can be seen close to the cluster core.

Large galaxies, though comparatively immune to ram-pressure stripping, also tend to die in clusters. During their assembly, they experience numerous merger events and tend to develop large central black holes, which develop into brilliant quasars. Mergers efficiently convert gas to stars while quasar activity removes gas from the galaxy, causing star formation to cease quickly.

Naturally, the Mira Cluster is abnormal here too. It has 47 galaxies with a mass of more than 1 trillion solar masses, which is the limiting mass where quasar feedback and mergers force most galaxies into a red-and-dead state. In the Virgo Cluster, this population is represented by the likes of Messier 60 or Messier 87, while in Mira we instead find enormous spirals like Helianthus and Amborella. The former is the most egregious case of all; it spans some 700,000 light-years and weighs in at over 20 trillion solar masses, yet continues to form stars like nothing is amiss.

Clearly something odd must be afoot.

The giant spiral galaxy 2MASXJ16014061+2718161. This galaxy is the largest member of a rich cluster and has regenerated a spiral disk through a merger. Helianthus is quite similar though Mira is younger than this cluster.

The paradox of youth in Mira’s giant members is resolved by mergers, strangely enough. There are several signs that the Mira Cluster experienced a wave of major mergers within the last billion years. The density of orphan stars and globular clusters scattered between its galaxies is abnormally high, many of its galaxies have binary supermassive black holes or stripped-down ultra-compact dwarf galaxies in orbit, and around one in ten of its galaxies displays obvious merger-induced disturbances. Mira’s population of large galaxies may have been up to 20% higher a billion years ago.

Mergers typically reduce star-forming rates through the consumption of gas, but particularly gas-rich mergers can rescue star formation in a red galaxy and form a new disk. Many of the large Mira spirals do appear to be ‘born-again’; Helianthus has a giant stellar halo like cD supergiant ellipticals (ergo ESO 383-76) despite being a spiral, while the core of Calamus is literally just a normal elliptical galaxy.

However, merger-induced rejuvenation is normally a short affair for large galaxies, since much of the gas volume fuels the central supermassive black hole and shuts down star formation again. While the less massive Mira giants have smaller black holes and so do not experience this feedback as severely, the largest must circumvent it somehow.

Key to this mystery is the elliptical galaxy Alternaria. Though barely over a thousand light-years wide, it is extremely bright, outshining many cluster members 50 times its size. Though this is not inconceivable for an ultra-compact galaxy, around 90% of Alternaria’s mass is in the form of a 20 billion solar-mass supermassive black hole. This could not possibly have formed inside such a small galaxy; indeed, the only galaxy large enough to possess such a giant central black hole is Helianthus, which conveniently lacks one. It seems that Alternaria is actually the core of Helianthus, stripped in an ancient collision and left to wander the intergalactic void.

If a galaxy loses its central black hole, it will take more than the age of the universe to regenerate it, especially one this large. With little hope to be captured by another galaxy, black holes ejected into intergalactic space can wander essentially forever. Besides Helianthus, the giant spirals Aechmea, Heliomeris, Entoloma, and Gleichenia are all devoid of supermassive black holes, suggesting this is a common process in the Mira Cluster. The ‘homeless’ quasar Opostomias also suggests that black holes can escape their host galaxies as it is currently leaving its erstwhile host, the giant elliptical galaxy Lycoris.

The End of Greatness

The ‘jellyfish galaxy’ PGC 2456, which lies in the galaxy cluster Abell 85 700 million light-years away from Earth. Ram pressure from the intergalactic medium will eventually strip every cluster’s galaxies of their star-forming gases. Many of Mira’s members display similar features.

Even with all its peculiarities, Mira lives on borrowed time.

Though the largest members of Mira will continue to survive for hundreds of billions of years, the vast majority of its members will not be so fortunate. The spectacular tails of the galaxies Byblis, Argyroxiphium, and Aecidium portend the end of their star-forming lives as their supplies of gas are ripped out. Many others have already been drained of all they have, joining a steadily growing contingent of old galaxies. Even Milky Way-sized Halimeda and Robiquetia are dead, stripped bare after dozens of plunges through the hot cluster core. One day, all the remaining star-forming galaxies will join them.

Nor will the power of mergers abate. Most galaxies in the cluster have relative velocities great enough to escape each other’s mutual pull, but dynamical friction will pull all of them to the core eventually. Over tens of billions of years, the inhabitants of this grand galactic hunting ground will become ever fewer in number until only bloated Helianthus is left. Gravitationally alone, it will slowly use up its gas and fade away, just like every other galaxy in the universe.

But in the cosmos, even an ephemeral moment can seem like an eternity.